Governor Hotel

|

The general reaction is, what the hell, and I'd say that's a completely valid reaction. In his guide to Portland architecture the usually reliable Bart King doesn't seem to swallow the explanation of the Governor's spacemen as "Vienna Secessionist" one little bit. The Governor Hotel's own web site steps smilingly away from the whole problem: At the top of the Governor building are interesting and seemingly out of place features in contrast to the more subdued structural embellishment. Some believe these designs to be “robots” while others believe them to be more abstract and not intended to be anthropomorphic at all. Whatever the case, these ornamentations certainly provide fodder for entertaining discussion. Yes, they are mysterious. Yes, they're the most significant part of the building, maybe nationally significant. Yes, they're figural sculptures, and I have a full explanation. Originally the Seward Hotel, opened 1909, architect William Christmas Knighton. According to Bosler and Lencek's Frozen Music, Knighton was born in Indianapolis and worked in Birmingham (Alabama, not England) and Chicago before coming to Salem in 1893. After a brief return back east, he became the State Architect in 1912. |

|

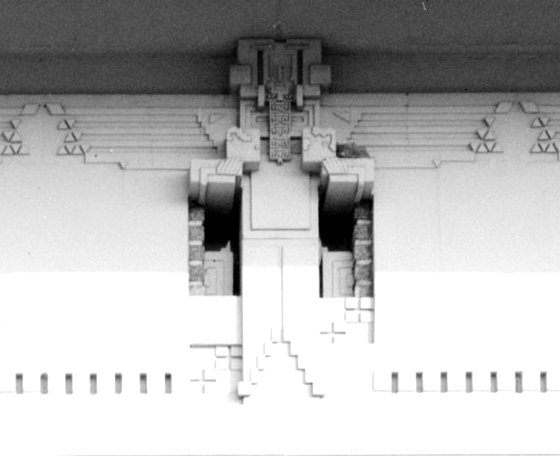

Among his other work in the area is one of those poured-concrete courtyard apartment houses at 117 NW Trinity, just north of PGE Park across Burnside, dating from 1910 and showing a vague family resemblance to the Governor. There's also the Oregon Supreme Court Building in Salem, 1914, and the very straightforward Grant High School (1923). Nothing else nearly like this. This is Knighton's big moment of idiosyncrasy. And it's a doozy. Along the roofline of this five-story hotel there's this line of fourteen barely-recognizable cubist figures, or 'spacemen', or 'Transformers,' in glazed terra cotta, seven on one side, another symmetrical seven on the other around the corner. Somehow they're plainly male. There are two alternating varieties. The bigger ones have a recessed square of tile in varied shades of blue (maybe translucent?) and a stylized twisted penis. The smaller ones have bell-shaped legs. Both kinds have the same geometric face, a vertically oriented lozenge within a narrowing trapezoid box, that turns out looking oddly simian around the "eyes". That same stylized face is repeated along the roofline, too. |

|

And it's all ridiculous. They're gratuitous, they're in a posture as if they're hung there to dry, and they seem so proud of themselves. Unlike a lot of architectural sculpture the spacemen aren't trying to convince you of one thing or another, they don't come with identities or associations. The spiritual soul-brother of the Governor Hotel is the little-discussed F.C. Bogk House back in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a design of Frank Lloyd Wright's. It's a private residence, a late and strange example of Wright's fascination with geometric ("architectonic") figural sculpture integrated with architectural form. The Bogk House carries four patterns under the eaves on the facade that, when you look, resolve into four male figures with outstretched arms, faces, and outspread wings. They're also awkward. More than a little awkward. They're not going to make the cover of the next FLW calendar. Wright took artistic risks. Not all of them worked out.

Wright also experimented with geometric human figures at the Larkin Building in Buffalo and the Dana-Thomas House in Springfield Illinois, but artistically the most successful examples were the sprites at the Midway Gardens beer garden in Chicago, built in 1913, where Wright and sculptors Richard Bock and Alfonso Iannelli produced a set of conventionalized figural variations for "Cube" (male), "Octagon" (male), "Triangle" (female), "Totem Pole" (male), and "Sphere" (female, not stylized at all). These became fairly well-known at the time but Wright had a hard time sharing credit for those sprites with Iannelli. Both Bock and Iannelli got a little tired of Wright claiming all the credit and ended their collaborations. At the Bogk House, three years later, Wright tried to do the sculptural work by himself. |

|

Both Wright and Knighton were responding to a common source, the architectural sculpture work in the "Vienna Succession" (aka "Jugendstil", actually all around Europe, different names in different countries) around 1900. It was all terribly modern and distorted and shocking and new. Many of those innovations are traceable back to a specific source, the sculptor Franz Metzner, who invented a bunch of new relationships of figure-to-building, like conventionalizing figures, and mixing scales for dramatic effect, and cramming muscular figures into tight rectangular architectural frames, giving them a sense of potential energy like coiled springs. Metzner's probably the greatest sculptor nobody's ever heard of. Wright met him during Wright's mysterious year-long European vacation, and Metzner is one of the very few people Wright ever admitted being influenced by. Metzner is also name-checked in Sacramento, of all places, where the local architect Rudolph Herold paid homage to, or stole, Metzner's guardians in the Crypt of the Völkerschlachtdenkmal in Leipzig by reproducing them, in terra cotta, on the Sacramento Masonic Temple, 1913-1918. Another of Metzner's wonderful and bizarre experiments in the relationship of figure-to-building can be seen at Jose Plecnik's 1905 Zacherl House in Vienna where a line of hunched and highly stylized atlantes support the cornice with their necks.

So the fourteen Transformers dangling from the Hotel Governor in downtown Portland have the same European lineage. Are they a success? Well, they have no function other than advertising themselves. We're still talking about them 100+ years later. So the answer is yes, they work great. |

Copyright 2010 Walt Lockley. All rights reserved.