|

The Great Sign

|

I had a childhood in motels, growing up in the friendly confines of the leather back seats of a couple of company cars, a green 1972 Buick Electra with white leather and a pumpkin-colored 1974 Cadillac Eldorado with pumpkin-colored leather, criss-crossing the continent, and sleeping in Holiday Inns. Every morning at breakfast, Dad would pull out his

itinerary from this briefcase, and pull out the thick national paperback

Holiday Inn guide from its transparent stiff mylar bracket in the

middle of the restaurant table next to the jelly caddy, and decide

that tonight would be Van Wert, or Sundance, or Cortland, or whatever.

I loved to look at that national guide and its small location maps

with a collect them all frame of mind. Dad would make the next

night's reservations at the front desk through their Holidex system,

back when networked computers were objects of wonder and fear, and

then we'd finish breakfast, repack, and hit the road. |

|

These were the good years for Holiday Inn. They were the first national motel chain and they had a lock on the industry for years in an invincible network of small towns and outskirts. No need to stay anywhere else. Casper Wyoming room 213 and Van Wert Ohio room 107, or any two Holiday Inn rooms chosen at random by Holidex, were indistinguishable like two cross-section slabs of interstate concrete, and the psychological effect was to reduce the Holiday Inn room to an abstract, a placeless ideal. (Picture Dad checking the phone book cover or calling down to the front desk first thing to find out where the hell he was.) This kind of existential nightmare was profitable and the only organized competition was Ramada, and they weren't worth bothering about. Holiday Inn was like a utility in the late 60's, an untouchable utility, with new properties sprouting up overnight at major intersections like Wal-Marts did ten years ago. A great success story, a powerful brand, a cash machine. I was a kid, and an oblivious kid at that. So I have vivid and fond memories of specific sensations, like the bit of shiny curled foil separated from the top of the strawberry jam packages, and the small aluminum burrs on the unsmoothed door jambs that would catch the flesh of your fingertips if you weren't careful, and the supercold metal ice scoop in the humming ice machine, and the wide brown elastic bands under the two chairs, and the sanitary strips on the toilet seat, the taste of swimming pool water, local newscasters from other cities always different and always the same, and after bed the overnight concert of highway noises especially if the motel was close to a bumpy overpass on a major road (it always was), and that weird sensation of always being somewhere else in the same place, a sensation I've never been able to shake. The most magic part, though, was -- The Sign. |

|

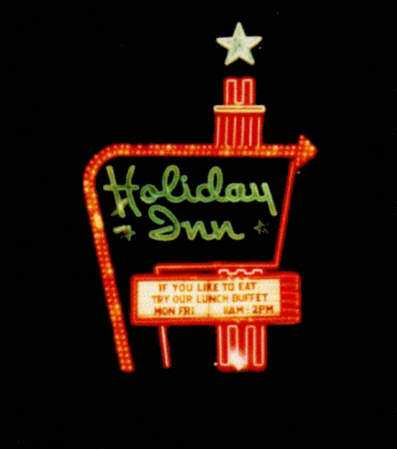

The Sign.

With an orange neon column supported a field of green; the green field was bordered on the outside and top by a high yellow arrow which helpfully pointed toward the motel. The words 'Holiday Inn' were written on that field of green in that stylized cursive. Below the letters was a white rectangle where the maintenance man hung letters like 'MEXICAN BUFFET 3.95' or 'FREE COLOR TV'. There was a curved orange bulkhead around the white rectangle, hugging the ground. And a holy white star surmounted the orange column with its own cartoony markings of radiance, see photograph. I remember one night in particular, after driving 300 north miles across Texas from San Antonio at night, coming into Waco from the south. The Waco property was on a big hill next to the highway, and you could see that big recklessly attractive hyperkinetic green neon from fifty miles away, first as a tiny detail in the endless Texan darkness, an illusion intermittently blotted out by night, real then not real, then a live possibility. Are we almost there? One thing Holiday Inn learned from the small-town motels they drove out of business was this: a motel needs a big, bright sign. The collision of the Holiday Inn chain and the neon tradition of the individual motel sign produced this American icon, this hypnotic visual splash, part of the postwar atomic-futurismo roadside architecture of transport, born of that world of interstate highways, drive-in movies, service stations, 'googie' coffeeshops and motels. I remember approaching its mystical attraction and touching it, wondering if I would make the magic leak out. According to a short article in the August 1983 Harper's, it took 426 light bulbs and 836 feet of hand-blown neon tubing to achieve that postwar exuberance. Holiday Inns, Inc. referred to it as 'The Great Sign' in the 1983 press release, the press release which announced they were junking it, nation-wide, for a dumpy brown rectangle which was corporate Holiday Inn's agonizingly lame excuse for a replacement. |

|

This Great Sign, as wonderful as it

is, was only the standardized and widely replicated version of the older

and more exciting independent motel's signs which were all over the

continent. The Holiday Inn sign was dull compared to fabricated illusions

for motels called The Continental, The Riveria, Castaways, Caravan,

Trade Winds, El Rancho, things like that, like the famous 1934 Steele's

Motel sign from Los Angeles, featuring a girl neon diver, who twists

in three consecutive positions before disappearing into the pool over

and over and over. I think it's her persistence that's so attractive.

The signs were crazy gestures, exuberant, ecstatic, extra-ordinary and vulgar, especially in contrast to the other features of these withered midwestern towns, and after a long dose of road-hypnosis on the dark highway, after 100 empty miles of the murky darkness of midnight flatland Texas, that thing would just crash into your eyes. It was a lighthouse that meant an empty bed just for you, free ice, color TV, sleep -- a nuclear ice palace in a desert of darkness, a clear indication of paradise, satori in Van Wert.

In the morning daylight, if you stood across the street and looked carefully, you could see that the motel building and the motel sign were locked in a death grip. Visually and functionally they were exact opposites who hated each other but needed each other to survive. You know, like GM and the UAW. The sign was a creature of speed and fantasy and illusion. The sign stood up proudly and belonged to the road. The sign presented a whole nonsensical and liberating illusion about the motel, its fantasy-oriented identity captured in the name and the neon . Only then could you find Camelot in Tulsa ("firetrap" Mom said). The Riveria, The Tropical Inn, Castaways, Caravan, Trade Winds, El Rancho. The sign didn't appear to be materially real, much less economically real, and in its scale aimed to the highway it seemed superhuman, what, 25 or 30 feet up. The motel, on the other hand, was a thing of restrictive utility and permanent hard fact. It was horizontal and inconspicuous. It belonged to the town. The technical term for a one-story-individual-exterior-room-entry motel shape is "down-and-out". The motel buildings were uniformly concrete and steel construction, cut-rate International styling, colored masonite panels on aluminum grids, etc. Brutal economic reality was obvious inside and out and this thing about The Riveria? El Rancho? Whopping lies. An illusion was the only identity this building could claim. Hard put to find anywhere on the Riveria or the Mexican frontier where the t.v. was bolted to the dresser, the hangers were unstealable, the table bolted to the floor, and the guests trusted only what wasn't worth stealing, like the Bible. |

|

And that was a long time ago. Corporate misjudgements, determined competition, and OPEC reduced Holiday Inn to a smaller niche in the industry. By about, um, 1976, the Holiday Inn monopoly slipped

through their fingers, and the company had a nervous breakdown. The

original signs came down, traded in for a brown rectangle with rounded

corners, a design that is physically difficult to even focus on. Then

came "The Best Surprise Is No Surprise", deathless promise

of diminished expectations, aimed more to employees than guets. Right

now Holiday Inn stays alive only because of real estate tax law, and

brand recognition which is still incredibly high in the 50-80 ages

relative to all competitors. |

Copyright 2006 - 2010 Walt Lockley. All

rights reserved.